Introduction

The liver is the largest internal organ in the body and has many important roles, such as aiding digestion, metabolism, and clotting. It weighs roughly 1.5 kg and is located in the right upper quadrant (RUQ). In the clinical setting, doctors regularly order liver function tests (LFTs) for patients and imaging like ultrasounds to assess its function. This page will discuss the anatomy of the liver, clinically relevant conditions, and the interpretation of liver blood tests.

Position

The liver lies under the diaphragm in the right hypochondrium and epigastric regions. It is an intraperitoneal organ, meaning that it is wrapped within the visceral peritoneum (a serous membrane lining the abdomen).

Glisson’s Capsule

The liver is surrounded by a fibrous layer called Glisson’s Capsule. This is a layer of interstitial connective tissue and covers key vessels like the hepatic artery and portal vein. When the liver becomes inflamed, it outstretches this capsule, causing pain and discomfort.

Lobes and Ligaments

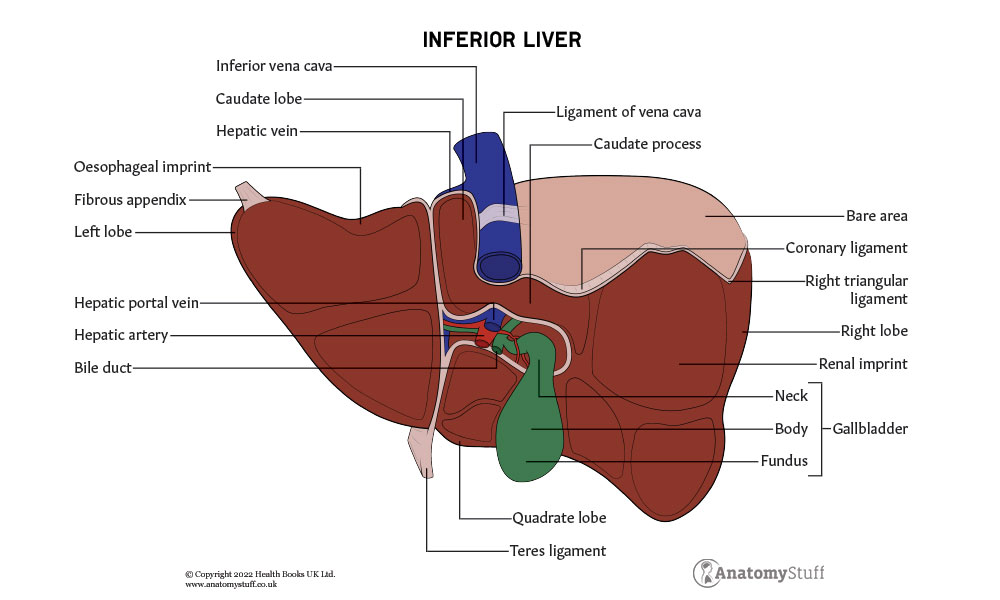

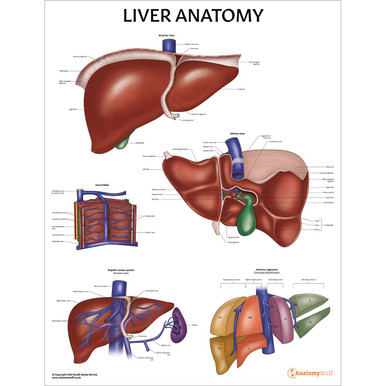

The liver can be divided into 4 lobes:

• Right lobe (largest)

• Left lobe

• Caudate lobe

• Quadrate lobe

When viewed from the front (anteriorly), the left and right lobes can be seen. They are separated by a band of connective tissue called the falciform ligament that anchors the liver to the abdominal cavity.

Other ligaments in the liver include:

• Coronary

• Triangular

• Round

• Hepatogastric

• Hepatoduodenal

• Ligamentum venosum

Surfaces

The liver has 2 surfaces:

1) Diaphragmatic – the anterosuperior surface of the liver, which fits under the curvature of the diaphragm.

2) Visceral surface – posteroinferior surface, which shows lots of impressions of neighbouring organs and structures.

Associated structures

The gallbladder is located on the visceral surface of the liver, lying within a small hollow formed between the inferior aspects of the right and quadrate lobes of the liver. It is a temporary storage for bile (an aqueous solution produced by the liver).

The inferior vena cava (formed by the confluence of the right and left common iliac veins at L5) passes through the posterior surface of the liver before entering the thorax. Find out more about the anatomy of the vena cava here.

Vascular supply

The liver is a highly vascular organ. It receives a mixture of both arterial and venous blood, with roughly 1500ml of blood uniting every minute while entering the liver.

The liver receives blood from two sources (a dual blood supply). This consists of the hepatic artery, which supplies the liver with oxygenated blood, and the hepatic portal vein, which delivers deoxygenated, nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine. The blood also carries medication and toxic substances, which are then processed by the liver.

The common hepatic artery arises from the coeliac trunk. It divides and splits into the proper hepatic artery and the gastroduodenal artery. The proper hepatic artery then enters the porta hepatis, where it splits into the left and right hepatic arteries that supply the liver.

The portal vein contributes to roughly 75% of the liver’s blood flow. It is formed by the union of the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein and drains the blood from the gastrointestinal tract (except the lower section of the rectum), gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen to the liver.

The hepatic vein then drains the deoxygenated venous blood from the liver into the inferior vena cava. The main hepatic veins are the right (longest one), intermediate and left hepatic veins.

Portal triad

As discussed above, the liver receives blood from 2 sources: the hepatic artery and the portal vein. These vessels run alongside branches of bile ducts within structures called portal triads.

To summarise, the triad contains:

1) Branches of the hepatic artery carrying oxygenated blood to the hepatocytes.

2) Branches of the portal vein carrying nutrient-rich blood (mostly deoxygenated) from the small intestine.

3) The bile ducts carrying bile products to the gallbladder.

Nerve supply

The liver is innervated by both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems (part of the autonomic nervous system). The hepatic plexus contains sympathetic (coeliac plexus) and parasympathetic (vagus nerve) nerve fibres.

Refresher

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is divided into the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. The somatic nervous system controls voluntary muscular systems within the body, consisting of motor (efferent) and sensory (afferent) nerves. It is also responsible for the reflex arc. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary physiologic processes, including digestion and respiration. It can be divided into the sympathetic (‘fight or flight’), parasympathetic (‘rest and digest’) and enteric systems.

Lymphatic drainage

The liver is the largest lymph-producing organ in the body, accounting for approximately 25 to 50 % of all lymph flowing through the thoracic duct. The lymphatic drainage consists of the deep system (made up of hepatic lymph vessels) and the superficial system (transports lymphatic fluid through channels in Glisson’s Capsule).

Refresher

The lymphatic system is the body’s drainage system. It helps to maintain fluid balance, enhances the immune system and facilitates the absorption of dietary fats into the bloodstream for metabolism or storage.

When blood plasma (the liquid component of blood containing over 700 proteins and other substances) escapes, it becomes interstitial or extracellular fluid. Most of this fluid re-enters the bloodstream, but some is left behind, now becoming ‘lymph’. Once within the lymphatic system, the lymph drains into larger vessels called lymphatics. These contain lymph nodes which filter lymphatic fluid by removing foreign materials. When the lymphatics converge, they form 2 large vessels called lymphatic trunks; the right lymphatic duct (which drains the upper right portion of the body) and the thoracic duct (which drains the rest of the body).

Cellular

There are 4 main types of cells found in the liver.

1) Hepatocytes – important epithelial cells which make up roughly 80% of the liver mass. They are involved with the basic functions of the liver like detoxification, bile section and metabolism. The hepatic or liver lobule is a hexagonal collection of hepatocytes. A portal triad (portal vein, hepatic artery, bile duct) sits at each of the 6 corners. The human liver is estimated to contain approximately 1 million of these classical hepatic lobules.

2) Kupffer cells – resident macrophages of the liver (highly specialised immune cells which originate from monocytes and undertake phagocytosis to engulf pathogens).

3) Hepatic stellate cells – play an important role in vitamin A and lipid storage.

4) Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells – separate blood for filtering by hepatocytes.

Refresher

Epithelial cells cover the outer surface of the internal organs and the body. On the other hand, endothelial cells line internal pathways, such as the inner surface of blood vessels.

Functions of the liver

The liver has many life-sustaining functions within the body.

The main ones include:

1) Production of bile – The liver produces this aqueous solution made from bile salts, phospholipids, cholesterol, conjugated bilirubin, electrolytes, and water. The bile travels out of the liver to the gallbladder for storage.

2) Production of cholesterol – Cells in the body can directly synthesise cholesterol; the liver is the primary location for this crucial process.

3) Blood sugar balance – The liver produces, stores (through a process called glycogenesis in which the liver converts glucose into glycogen) and releases glucose depending on the body’s needs.

4) Storage of vitamins – The liver stores vitamins A, D, E, K and B12. The bile secreted during digestion is essential for absorbing the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

5) Protein synthesis/clotting – Albumin is the most abundant protein in the blood and is made exclusively in the liver. The liver also synthesises most of the coagulation cascade, and fibrinolytic pathways are necessary for blood coagulation with the help of vitamin K.

6) Detoxification – The liver is vital for the detoxification of endogenous substances (produced by the body, such as ammonia) and exogenous substances (like drugs and alcohol).

7) Metabolism – The liver cells break fats down to produce energy. They also break down heme (a protein in red blood cells) through a process called haemolysis, and the by-products are biliverdin and bilirubin.

8) Immunity – The liver contains the largest collection of phagocytic cells in the body (Kupffer cells) to detect, capture, and clear bacteria, viruses, and macromolecules. It also produces acute-phase proteins, which are an integral part of the immune response.

Clinical relevance

Liver Function Tests (LFTs)

Doctors will often order LFTs to assess a patient’s liver. They are one of the most commonly ordered blood tests, both primary and secondary care. This blood test consists of the following:

• Alanine transaminase (ALT)

• Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

• Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

• Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT)

• Bilirubin

• Albumin

• Prothrombin time (PT)

ALT is a marker of hepatocellular injury, whereas ALP is a marker of cholestasis (when bile flow is blocked).

It is important to note that the bones also contain high levels of ALP. Therefore, a raised result can be a marker of bone diseases like Paget’s or bone metastasis (when cancer cells spread from their original site to a bone).

Liver Pathologies

Liver disease accounts for hundreds of deaths each day. There are many different causes, including genetics, viruses, alcohol use and obesity. Over time, conditions that damage the liver can lead to scarring (cirrhosis), which can then result in liver failure. One key sign of liver failure is a condition called jaundice which is the yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes, and sclera (whites of the eyes). It occurs when excess amounts of bilirubin circulating in the bloodstream dissolve in the subcutaneous fat. Another detrimental complication of liver failure is portal hypertension which is elevated blood pressure in the portal vein. It occurs due to increased intrahepatic vascular resistance to the portal flow. Consequently, swollen veins called varices develop within the oesophagus, stomach, and rectum. Without treatment, these varices can cause severe bleeding, often leading to death, which is often a common emergency medicine scenario.

Portal hypertension can also lead to ascites, a lymphatic, protein-containing fluid that leaks from the surface of the liver and intestine and accumulates within the peritoneal cavity (a potential space found between the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum). Patients with severe ascites will have a large, distended abdomen, and there can be serious complications, such as an infection called spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Related Products

View All