Introduction

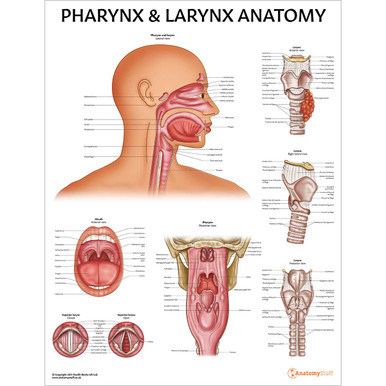

The pharynx and larynx are two important organs found within the upper respiratory tract. The pharynx (or throat) is a cavity that connects the nose and mouth to the larynx and oesophagus. The larynx, which merges into the trachea, is also known as the voice box because it contains the vocal chords. This page will discuss the anatomy of the pharynx and larynx, as well as relevant conditions affecting these organs, such as tonsilitis and vocal chord dysfunction.

Pharynx

Function

The pharynx (also known as the throat) receives air from the nasal cavity and air, food and water from the oral cavity.

It, therefore, plays an important role in the human body’s respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. The six pharyngeal muscles (discussed in more detail below) facilitate fundamental processes like speaking and swallowing.

Location

The pharynx begins posterior to the nasal cavity and travels inferiorly, where it meets the larynx and oesophagus.

Anatomy

The pharynx, which is roughly 12-14cm long, is a muscular, cone-shaped passageway. It can be divided into 3 segments: the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx, with each section playing its own important role:

• Nasopharynx – the superior part of the pharynx, which extends from the skull base to the soft palate. Important connecting structures and communications include:

Nasal choanae – paired openings that connect the back of the nose to the nasopharynx. They are separated by the nasal septum.

Eustachian tube – a tube that connects the middle ear (tympanic cavity) to the lateral wall of the nasopharynx.

Adenoids – a mass of lymphatic tissue present in the superior aspect of the nasopharynx medial to the eustachian tube orifices.

Oropharynx – the middle segment of the pharynx extending from the soft palate to the upper margin of the epiglottis. The walls are lined with squamous epithelium, just like the soft palate.

• Laryngopharynx – the inferior portion of the pharynx, also known as the hypopharynx. It extends inferiorly from the vallecula (potential spaces anterior to the epiglottis) to the cricoid cartilage at the vertebrae level of C6.

Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring is an incomplete ring of lymphoid tissue found in the naso- and oropharynx. It is considered the first line of defence against external, inhaled pathogens, so it plays an integral role in the body’s immune system. Structures within this ring include the tonsils, adenoids and other lymphoid tissue.

Pharyngeal muscles

There are six major pharyngeal muscles which form the lumen of the pharynx and aid with life-sustaining processes such as breathing and swallowing. They can be divided into two groups; two the outer circular layer and the inner longitudinal layer.

The outer circular layer consists of the superior, middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle further divides into two additional muscles: the thyropharyngeus and the cricopharyngeus. The inner longitudinal layer consists of the palatopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus and stylopharyngeus muscles (these are paired).

The constrictor muscles (superior, middle, and inferior) contract to propel food into the oesophagus (peristalsis). Clinically, if there is incoordination of contraction and relaxation of the thyropharyngeus and the cricopharyngeus muscles, intrapharyngeal pressure can rise, and a diverticulum can develop between the weak spot of the two muscles. This structure is called Zenker diverticulum food can accumulate in the pouch, leading to swallowing difficulties (dysphagia).

The paired muscles of the inner longitudinal layer (palatopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus and stylopharyngeus) widen and shorten the pharynx to move food into the oesophagus and elevate the pharyngeal wall to protect the airway.

Vasculature

The pharynx has a rich arterial supply, with all arteries originating from the external carotid artery. The major arteries include:

• Ascending pharyngeal artery

• Facial artery (branches)

• Lingual and maxillary arteries (branches)

The venous drainage of the pharynx is via the pharyngeal plexus, which drains into the internal jugular vein.

Innervation

The pharyngeal plexus provides motor and sensory innervation to the majority of the pharynx. This plexus, which is located on the posterolateral wall of the pharynx, is formed from the union of different branches from the:

• Vagus nerve

• Glossopharyngeal nerve

• Superior cervical ganglion

The vagus nerve provides motor innervation to all pharyngeal muscles except from the stylopharngeaus muscle (which is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve).

The pharynx receives the majority of its sensory innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve. The exceptions to this are:

• The larnhopahryx (innervated by the vagus nerve)

• The anterior and superior aspect of the nasopharynx (innervated by the maxillary nerve)

Larynx

Function

The larynx has 4 main functions:

• Breathing

• Swallowing

• Phonation (production of sound)

• Airway protection

It prevents unwanted food and particles from entering the lungs by closing off the trachea (temporarily halting respiration) and opening the oesophagus.

Location

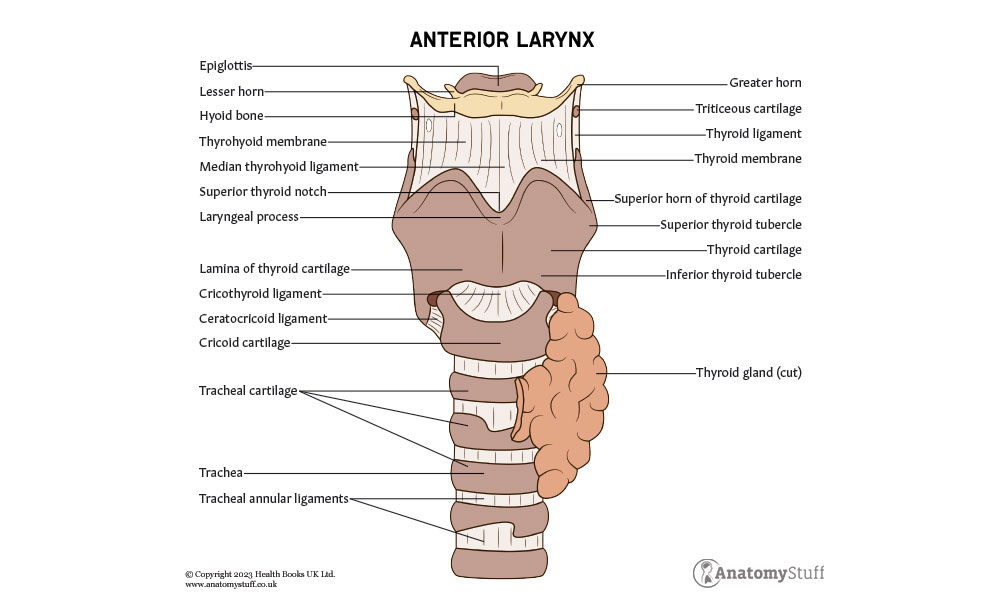

The larynx is a cartilaginous structure located within the anterior compartment of the neck. It continues with the pharynx superiorly and the trachea inferiorly.

The hyoid bone is a C-shaped structure that anchors the larynx during respiration and phonation. It also serves as an attachment structure for the tongue and muscles from the oral cavity above and the epiglottis and pharynx behind. Clinically, a fracture of the hyoid bone can suggest strangulation.

Anatomy

The larynx can be separated into three distinct segments: the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis.

The middle section, the glottis, refers to the vocal apparatus of the larynx. It consists of the true vocal chords and the space between the vocal chords called the rima gottidis.

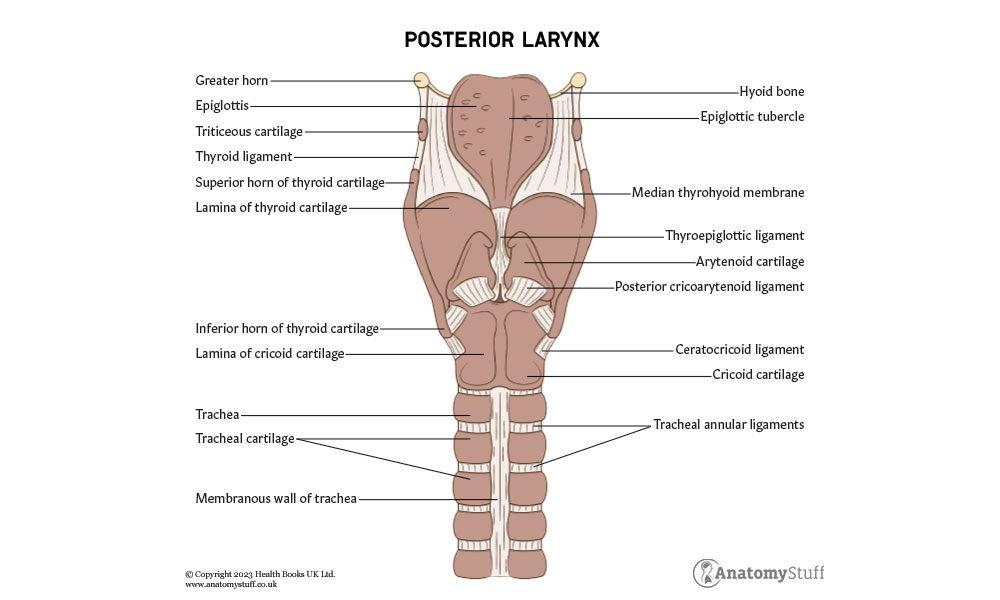

Cartilage

There are nine different types of cartilage located within the larynx; three large unpaired cartilages (epiglottis, thyroid and cricoid) and three paired smaller cartilages (arytenoid, corniculate and cuneiform).

1. Epiglottis – A leaf-shaped piece of elastic cartilage that covers the laryngeal inlet during swallowing to protect the airway.

2. Thyroid – Composed of hyaline cartilage and is the largest section of cartilage in the larynx. It sits beneath the hyoid bone.

3. Cricoid – Ring-shaped cartilage (completely encircles the airway) that sits below the thyroid cartilage.

4. Arytenoid – Paired pyramid-shaped cartilages made from hyaline cartilage. They articulate with the cricoid cartilage to facilitate movement of the vocal chords. Muscles involved with phonation are attached to their anterolateral surface.

5. Corniculate – Small, paired, elastic cartilages that articulate with the apices of the arytenoid cartilages.

6. Cuneiform – Small, paired elastic cartilage, also known as Wrisberg cartilage. They are located in the aryepiglottic fold (a mucous membrane that extends from the arytenoid cartilage to the epiglottis).

Refresher

Cartilage is the main type of connective tissue throughout the human body. There are three types of cartilage: hyaline cartilage, elastic cartilage and fibrocartilage. Elastic cartilage is highly flexible, and hyaline cartilage is the most abundant.

Ligaments

The larynx contains two types of ligaments: the extrinsic ligaments (thyrohyoid, hyoepiglottic and cricotracheal) and the intrinsic ligaments (cricothyroid, cricocorniculate, thyroepiglottic, thyroarytenoid and arytenoid epiglottic).

The extrinsic ligaments, as the name suggests, attach the larynx to nearby structures such as the hyoid and trachea. The intrinsic ligaments connect cartilage together within the larynx.

Muscles

There are two types of muscles found within the larynx: extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. The extrinsic muscle group contains infrahyoid and suprahyoid muscles. Examples are the daigastric, stylohyoid, geniohyoid and mylohyoid muscles.

The intrinsic muscles can be sub-divided further into two groups:

• Muscles that control the inlet of the larynx (by drawing the epiglottis down so that its lower half makes contact with the arytenoids, creating a protective seal): aryepiglottic, oblique arytenoid and thyroepiglottic muscles.

• Muscles that move and control the vocal chords: cricothyroid, thyroarytenoid, posterior cricoarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, transverse arytenoid (or interarytenoid) and vocalis muscles.

The intrinsic muscles can be categorised again based on their function and role in phonation:

• Lateral cricoarytenoid and transverse arytenoid = Pull the vocal folds together (adductors)

• Posterior cricoarytenoid = pull the vocal folds apart (abductors)

• Cricothyroid = stiffen the vocal chords (tensors)

• Thyroarytenoid and vocalis = relax the vocal chords (relaxors)

To create forceful speech, the cricothyroid muscle will stretch and tense the vocal ligaments. To create a softer sound, the thyroarytenoid muscle will relax the vocal ligament.

Vasculature

The blood supply to the larynx is from the superior and inferior laryngeal arteries. The superior laryngeal artery supplies the upper section of the larynx, specifically the epiglottis, supraglottic region, and superior vocal chords. The inferior laryngeal artery supplies the remaining sections.

The venous drainage of the larynx mirrors its arterial supply – the superior and inferior laryngeal veins drain into the superior thyroid and inferior thyroids veins, which then drain into the internal jugular and subclavian veins, respectively.

Innervation

The larynx receives both motor and sensory innervation via branches of the vagus nerve – cranial nerve 10 (CN10). The superior laryngeal nerve supplies mucosa from the epiglottis to the level of the vocal chords, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplies the mucosa below this point.

Clinically, it is important to be aware of which of these two branches supply the intrinsic muscles as damage, especially during thyroid and parathyroid surgeries, can cause vocal chord dysfunction—the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplies all intrinsic muscles except the cricothyroid. The external branch of the laryngeal nerve supplies the cricothyroid muscle.

Clinical relevance

There are many conditions and emergency scenarios involving the pharynx and larynx.

Firstly, in relation to the pharynx, the oropharynx is a common site of inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic diseases. A common presentation is a pharyngitis (sore throat) which represents inflammation of the oropharynx. The nasopharynx is much less often involved, except for the Chinese race, where nasopharyngeal carcinoma accounts for almost 20% of malignancies.

Secondly, as mentioned above, the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplies all intrinsic muscles of the larynx (except the cricothyroid). Therefore, damage to this important nerve can affect phonation.

Interestingly, when only one vocal chord is paralysed (unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy), the other one can compensate quite effectively. However, in bilateral palsy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, speech cannot occur. Additionally, emergency surgical intervention can often be required to restore the airway. A’ cricothyrotomy’ can be achieved, which involves inserting a needle through the cricothyroid ligament.

Related Products

View All