Introduction

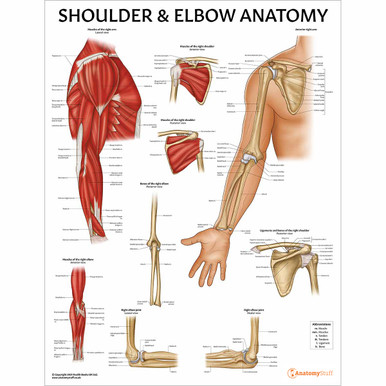

From lifting a chair to throwing a ball, our shoulder helps us perform a range of different actions in daily life. The shoulder joint, also known as the glenohumeral joint, is formed by the humeral head connecting with a depression in the scapula. It is supported by a complex arrangement of muscles and ligaments with an elaborate network of nerves and vasculature running through them. The clever and intricate anatomy of the shoulder joint enables it to be the most mobile joint of the whole body.

Osteology

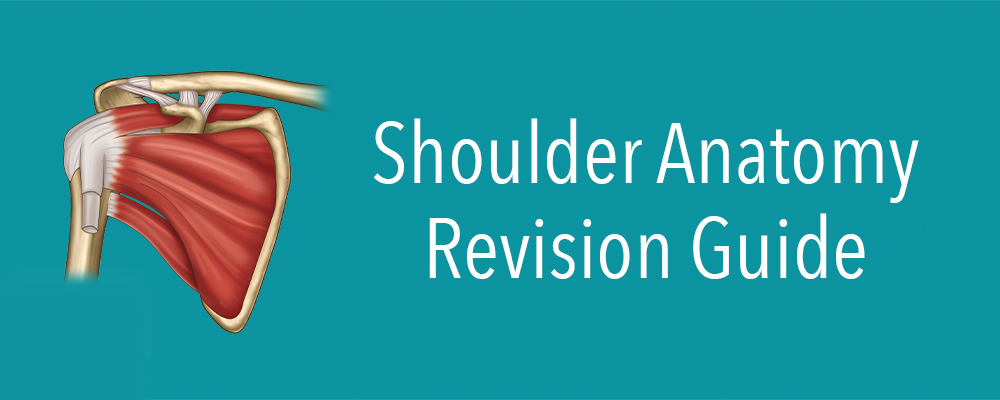

The glenohumeral joint is the site at which two bones articulate: the humerus and scapula. Whilst the clavicle is not directly involved in the formation of the joint, it is an attachment site for important ligaments supporting the shoulder.

The Proximal humerus

The distal end of the humerus is involved in the formation of the elbow joint, and the proximal end is in the formation of the shoulder. We will focus on the proximal humerus in this section.

The most proximal end of the humerus consists of a round-shaped head. The head is positioned medial, upwards and backwards, and this is the part that projects to the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

Underneath the head is the anatomical neck, and this separates the head from the greater and lesser tubercles. The lesser tubercle is smaller and medial. The subscapularis, which is a rotator cuff muscle, attaches here. The more lateral and larger the greater tubercle is where the other three rotator cuff muscles attach.

Between the two tubercles is the intertubercular sulcus. This is a groove through which the long head of the biceps brachii runs through. The pectoralis major, teres major and latissimus dorsi attach to the edges of the groove.

The surgical neck is underneath the tuberosities and above the shaft of the humerus. The axillary nerve and circumflex humeral arteries lie here.

Scapula

Colloquially known as the shoulder blade, the scapula forms the glenohumeral joint with the humerus and the acromioclavicular joint with the scapula. It is a triangle-shaped flat bone which consists of a costal surface, a lateral surface and a posterior surface.

The lateral surface of the scapula is the part which connects with the humerus.

Specifically, the humeral head sits in a shallow depression known as the glenoid fossa. Superior to the glenoid fossa is a small prominence known as the supraglenoid tubercle. This is where the long head of the biceps brachii attaches. Inferiorly is the infraglenoid tubercle where the triceps brachii attaches.

The costal surface mostly consists of a large depression known as the subscapular fossa, and this is where the subscapularis rotator muscle originates. The coracoid process is a hook-like projection on the superior and lateral sides of the costal scapula. It is the attachment site for pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis and short head of biceps brachii, as well as ligaments that support the glenohumeral joint.

The posterior surface consists of two large depressions, infraspinous fossa and the supraspinous fossa, and this is where the two corresponding rotator cuff muscles attach. Between these fossae running transversely is the spine. The spine projects into the acromion, which arches over the glenohumeral joint. The acromion can be easily palpated on a patient. The clavicle meets the scapula at its acromion forming the acromioclavicular joint.

Joint Type

The glenohumeral joint is functionally classified as a ball-socket type of joint. This is because the humeral head is round-shaped and moves within the shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula. A fibrocartilaginous ring known as the glenoid labarum covers the outer border of the glenoid fossa. This ring deepens the depression. Furthermore, the surface area of the humeral head is four times bigger than the glenoid fossa, and these specialised features allow greater freedom of movement in the shoulder.

The glenohumeral joint is structurally classified as a synovial joint. Like all synovial joints, the glenohumeral joint is enclosed by a joint capsule. This extends from the anatomical neck of the humerus to the border of the glenoid fossa. The outer layer of the joint capsule is made of tough fibrous cartilage, and the inner layer consists of a synovial membrane which secretes synovial fluid. This fluid lubricates the bony surfaces of the joint, so they move smoothly against each other.

Furthermore, the glenohumeral joint contains several synovial bursae. These are cushions filled with synovial fluid that reduce friction between tendons and joint structures. The major bursae of the glenohumeral joint are subacromial and subscapular.

Ligaments

The glenohumeral joint is strengthened and stabilised with the help of different ligaments which attach from the humerus, scapula and clavicle.

These include:

1. Coracohumeral ligament- runs from the coracoid process of the scapula to the greater tubercle of the humerus. This supports the most superior part of the joint and prevents inferior displacement of the humerus.

2. Glenohumeral ligaments- consist of three superior, middle and inferior ligaments which blend together with the joint capsule. These ligaments connect the humeral head to the glenoid fossa and stabilise the anterior part of the joint.

3. Transverse humeral ligament – runs between the two tubercles of the humerus and secures the long head of the biceps to the intertubercular groove.

4. Coracoclavicular joint- run from the clavicle to the coracoid process of the scapula. They maintain the position of the clavicle to the scapula.

5. Coracoacromial ligament- runs between the coracoid process and acromion of the scapula to form an arch overlying the glenohumeral joint. This prevents superior displacement of the humerus.

Musculature and movement

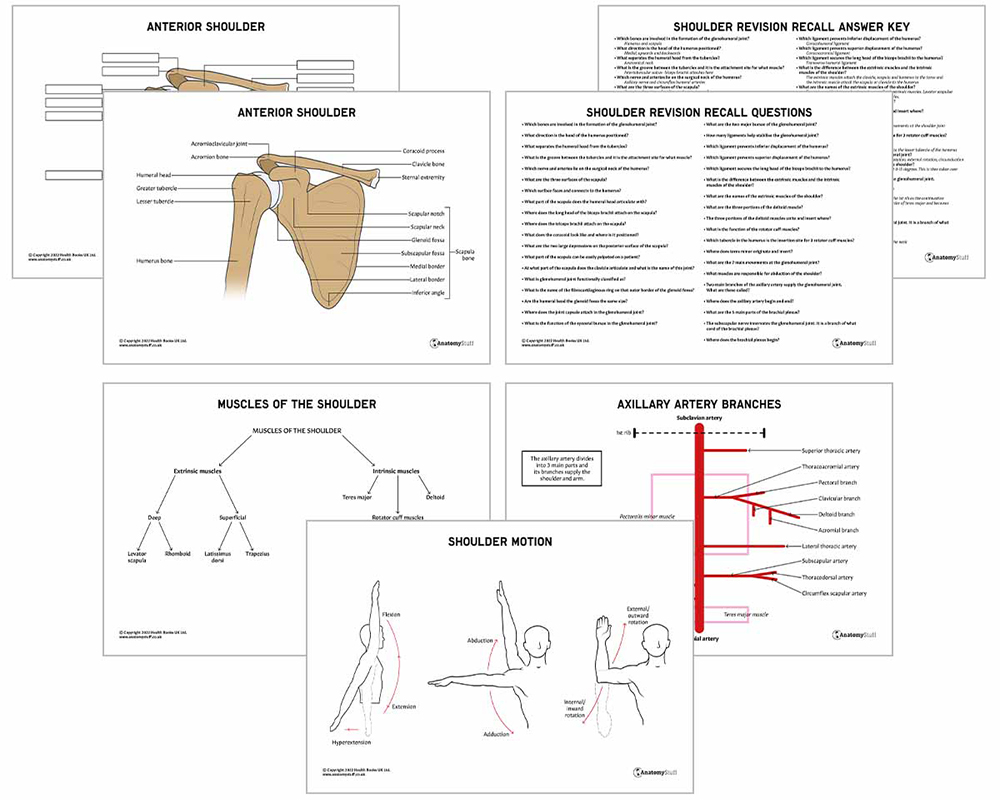

Whilst the main muscle of the shoulder is the deltoid muscle, movement in the shoulder is produced by a number of surrounding muscles working together. The muscles of the shoulder can be divided into extrinsic muscles and intrinsic muscles. The muscles of the pectoral region and upper arm also assist.

The extrinsic muscles attach the clavicle, scapula and humerus to the torso. These muscles can be into superficial and deep layers. The superficial extrinsic muscles are the trapezius and latissimus dorsi. The deep extrinsic muscles are the levator scapulae and rhomboid muscles.

The intrinsic muscles originate from the scapula or clavicle and insert into the humerus. These are the deltoid muscles, teres major and the four very important rotator cuff muscles.

The Deltoid Muscle

This is the largest and strongest muscle of the shoulder and provides definition and contour to the glenohumeral joint. The deltoid can be divided into three portions: anterior, middle, and posterior. The anterior originates from the superior anterior surface of the clavicle, the middle from the acromion and the posterior from the spine of the scapula. The three parts unite and insert into the deltoid tuberosity on the shaft of the humerus. The anterior deltoid is responsible for flexion and medial rotation of the arm. The middle abducts the arm once it is away from the side and the posterior part extends and laterally rotates the arm.

The Rotator Cuff Muscles

The rotator cuff muscles are the intrinsic and deepest muscles of the shoulder. They not only contribute to a range of different movements at the shoulder joint but provide stability. This is because they attach to the proximal humeral head and fuse with the joint capsule. This supports the glenohumeral joint by pushing the humeral head into the glenoid fossa.

The four rotator cuff muscles include:

1. Supraspinatus

a. Originates from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula

b. Inserts to the greater tubercle of the humerus

2. Infraspinatus

a. Originates from the infraspinous fossa of the scapula

b. Inserts to the greater tubercle of the humerus

3. Teres minor

a. Originates form the subscapular fossa of the scapula

b. Inserts to the lesser tubercle of the humerus

4. Subscapularis

a. Originates from the lateral border of the scapula

b. Inserts to the greater tubercle of the humerus

Movements

The glenohumeral joint is extremely mobile. The surrounding muscles of the joint are able to produce 7 main movements, and these are detailed in the table below:

| Movement | Description | Muscles involved |

| Extension | Move the arm back in the sagittal plane | posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi and teres major.

|

| Flexion | Move the arm forward in the sagittal plane | pectoralis major, anterior deltoid and coracobrachialis. A small contribution from biceps brachii |

| Abduction | Move your arm away from the midline | o The first 0-15 degrees of abduction are produced by the supraspinatus.

o The middle fibres of the deltoid are responsible for the next 15-90 degrees. o Past 90 degrees, the scapula needs to be rotated to achieve abduction – which is carried out by the trapezius and serratus anterior.

|

| Adduction | Move your arm towards the midline | pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and teres major.

|

| Internal rotation | Rotate the arm toward the midline so the thumb points inward | subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major and anterior deltoid.

|

| External rotation | Rotate the arm away from the midline so the thumb pointing outward | infraspinatus and teres minor.

|

| Circumduction | Move your arm in a circle | From a combination of above |

Vasculature

Arterial Supply

The anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries supply the glenohumeral joint. They are both branches of the axillary artery. The axillary artery begins at the lateral border of the 1st rib as the continuation of the subclavian artery. It ends at the inferior border of the teres major, where it becomes the brachial artery.

The suprascapular artery, which is a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, also has a small contribution.

Venous Drainage

The shoulder and arm are drained by the deep brachial veins, the basilic veins and the cephalic veins. These eventually drain into the subclavian vein.

Innervation

The subscapular nerve (C5-C6), which is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, innervates the glenohumeral joint. The joint capsule is innervated by several nerves:

• The suprascapular nerve innervates the posterior and superior part

• The axillary nerve innervates the antero-inferior part of the capsule

• The lateral pectoral nerve innervates the antero-superior part

Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerves in the shoulder region that sends signals from the spinal cord to the shoulder arm and hand. It is responsible for motor and sensory innervation of the upper limb. The plexus begins with the cervical spinal nerves C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 at the root of the neck, which continue to divide as they run through the upper limb. The plexus has 5 main parts: roots, trunks, divisions, cords and branches.

Related Products

View All