Contributor: Dr Patrice Baptiste

Edited by: Anne Marie Fogarty, RGN

Dr Baptiste Advises on OSCE Prep!

We recently met with Dr Patrice Baptiste, Portfolio GP, Medical Educator, Entrepreneur, Writer, and Speaker, to discuss all things Urinary Incontinence!

A hugely successful and well-known Portfolio GP, Dr Baptiste, talks about the OSCE prep: Obstetrics and Gynaecology Rotation: Urinary incontinence and prolapse.

Below we explore Dr Baptite’s in-depth advice around OSCE preparation to support students undertaking these exams.

OSCE – Awaiting the Exams

OSCEs don’t have been overwhelming! In fact, Dr Baptise (Patrice) believes they should be enjoyable and a way to demonstrate to the examiner that you have the knowledge and skill and that you know exactly what you are doing!

In her career as an OSCE examiner, Dr Baptise has seen many common mistakes that can be easily avoided. She generously shares this information with us today.

Watch the video below and smash your exams.

This video is part of an OSCE series which will help you tackle various topics across specialities. The first video in the series talks about urinary incontinence and prolapse – perfect if you are currently on an obstetrics and gynaecology rotation with exams around this topic coming up.

Urinary Incontinence and Prolapse

This article will discuss the following:

• The anatomy of the female pelvis

• The assessment of urinary incontinence and prolapse, including:

The type and severity of urinary incontinence

Causes and contributing factors

Complications

• Management, including examination and treatment

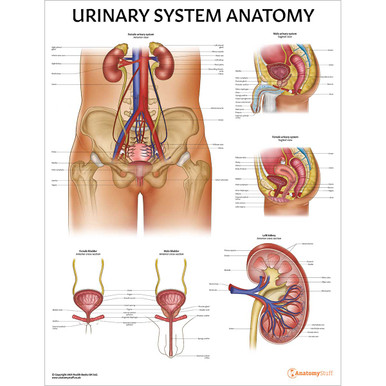

Before we look at urinary incontinence, here’s a little reminder of the pelvis anatomy.

The Anatomy of the Female Pelvis

There are three bones of the pelvis and some key bony landmarks such as:

Pelvic inlet – the female pelvis is circular, whereas it is heart-shaped in men.

• The posterior aspect is S1, plus each side of S1 is the alae or wings

• The lateral side is the prominent rim of the pelvic bone

• The anterior aspect is the pubic symphysis (two pelvic bones join in the midline)

Pelvic walls – There are two important ligaments connecting each pelvic bone to the sacrum and coccyx: sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

Pelvic outlet

• Anterior: pubic symphysis plus towards Ischial tuberosity

• Posterior: Sacrotuberous ligament (towards coccyx and sacrum)

Pelvic floor

• Separates the pelvic cavity from the perineum

• Levator ani (iliococcygeus/pubococcygeus/puborectalis x2) join together, plus the coccyges muscle are the pelvic diaphragm (they overlie the sacrospinous ligaments and pass between the sacrum /coccyx and ischial spine)

When these muscles become weak (due to pregnancy/childbirth, especially multiple pregnancies or being overweight), you can get symptoms of incontinence and prolapse (Keep reading – we talk about this later in the article).

Do you suffer from Urinary Incontinence? If so, read our related article here.

The Types of Urinary Incontinence

The International Continence Society defines incontinence as “the complaint of any involuntary urinary leakage.”

NICE guidance 2019 details the main types:

Stress – involuntary leakage on effort or exertion or when sneezing or coughing – we will focus on this type of incontinence in the video.

Urgency – involuntary leakage associated with or occurring before the sudden compelling desire to urinate, which is described as urgency (this is part of overactive bladder syndrome, which is urgency associated with frequency and nocturia. This can be divided into wet and dry, where the patient may or may not suffer from incontinence respectively).

Mixed – stress and urgency symptoms.

Overflow incontinence – this may be caused by

a) detrusor under activity (detrusor is a muscle which contracts and relaxes to release and help store urine respectively) or

b) bladder outlet obstruction means the bladder is unable to empty fully, therefore leading to the retention and then leakage of urine) – chronic urinary retention.

Continuous urinary incontinence – this might be caused by:

• A fistula (this is a connection between two body parts where there shouldn’t be one, for example, between the anal canal and vagina)

• The severity of their condition.

• Urethral diverticulum (a pocket or outpouching forms next to the urethra). This is a rare condition that you should be aware of.

Situational – depending on the situation, for example, laughing or intercourse.

Patient Assessment

In order to distinguish between the above types of urinary incontinence, you should ask the following questions during your history-taking:

Do you notice any urine leakage when coughing, sneezing, or exerting yourself?

Think stress incontinence

Do you feel the urge to rush to the toilet?

Urge + Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome

Do you need to use the toilet/pass urine frequently throughout the day?

Urge + OAB

Do you have to get up at night to pass urine?

Urge + OAB

If the patient’s symptoms seem to be a mixture of the above – so roughly an equal amount of urgency and stress, then this is likely to be mixed incontinence.

If symptoms occur without physical activity or a sense to rush to the toilet/urgency, then it is unlikely to be stress or urgency incontinence. If this is the case, then you should ask:

Do you feel you have to strain to empty your bladder, or do you feel as though you have not finished passing urine when you go to the toilet?

Overflow incontinence

Do you feel that you are constantly leaking urine?

Fistula e.g., vesicovaginal

Do you notice dribbling/pain when passing urine? / Do you have recurrent urine infections? / Do you have abnormal vaginal discharge / Do you have pain before/during/after sex/ sexual intercourse?

Urethral diverticulum

Severity

To determine how severe the urinary incontinence is, you should ask the following:

• How often does she suffer from incontinence – when does it occur (if she has identified a pattern), and is it associated with any particular activities or movements?

• Does she need to use incontinence pads – there are different sizes, so don’t forget to ask about this. How often does she change the pads or have to change her clothing?

• How often does she pass urine, during the day and at night?

• Bladder diary – NICE suggest three days at a minimum; this should include a variation in what she does each day to include different types of activities, for example, exercises and working pattern – it should include what type of fluid she drinks, how much and when.

Causes and Contributing Factors

To determine the cause and contributing factors of urinary stress incontinence, assess the following:

• Do you drink caffeine/coffee/tea /alcohol? And if so, how much?

• Obstetrics and gynaecology history.

• Sexual history.

• Red flags include haematuria or blood in the urine, ongoing bladder or urethral pain, recurrent UTIs, and constant leakage, which might suggest a fistula.

• Past medical history – medical conditions such as heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and neurological conditions that could cause incontinence, such as spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease. Cognitive impairment. Previous investigations or treatments for urinary tract issues and previous surgeries, such as spinal surgery.

• Medication history – are you taking any regular, OTC, or recreational drugs? There is a long list of medications that can cause or exacerbate symptoms, but a few examples to consider would be alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonists, such as doxazosin, antidepressants, diuretics, hormone replacement therapy, and benzodiazepines.

Management

Examination – you should always start with a general and then a closer inspection of the patient. You might want to look at the patient’s weight and body habitus and if there are any signs of neurological disease.

Abdominal examination

Complete as you usually would for a palpable bladder (chronic urinary retention) or a mass (cancer, fibroids).

Pelvic examination

• You should inspect for any skin changes, for example, signs of atrophic vaginitis, masses – prolapses (a pelvic organ prolapse is when one or more pelvic organs bulge into the vagina – it can be the uterus/bowel/bladder or top of the vagina), diverticulum which is a sac-like protrusion between the periurethral tissues and anterior vaginal wall.

• Ask the patient to cough and look at the urethral opening or meatus to see if there is any leakage or urine (stress).

• During the bimanual examination (where you insert two fingers into the ‘patient’s vagina to palpate the cervix and ovaries), you can ask the patient to squeeze your fingers (like they are trying to hold their urine) to check for muscle tone and contraction. This can be assessed using the modified Oxford grading system – allowing you to assess the strength of the contraction:

0 – no contraction

1 – flicker

2 – weak

3 –moderate

4 – good

5 – strong

A bedside test you could perform would be a urine dipstick looking for evidence of a UTI – leucocytes and nitrites. You might want to mention to the examiner that you would send midstream urine or MSU sample for culture whilst treating with antibiotics if you thought the patient had a urine infection.

Complications

Depending on the scenario, you could also consider the following:

• Renal function: Look for AKI or acute kidney injury if you suspect a urinary obstruction.

• Assessing for depression/quality of life could significantly affect the patient’s quality of life and mood.

• Asking about insomnia – if there are frequent trips to the toilet at night.

• An assessment of mobility or their risk of falling and potential fractures.

• Asking about their family/carers – how is this affecting them?

Treatment for Predominantly Stress Incontinence

• Address any causes or contributing factors as above.

• Lifestyle advice on reducing caffeine/fluid/weight and smoking cessation, if applicable.

• Provide sources of support and further information, such as the NHS website.

• The patient can be referred for a trial of 3 months minimum supervised pelvic floor training – this can be with a continence adviser or nurse specialist in urogynaecology, physiotherapist specialising in women’s health [guidance is a minimum of 8 pelvic floor muscle contractions at least three times a day].

• NICE CKS does not recommend things like absorbent containment products, i.e. pads and toileting aids, unless there are certain circumstances, such as waiting for assessment/ongoing treatment and for long-term management but only after other options have been considered/tried.

• If the above does not work, then a referral to urogynae/gynae or urology for surgical procedures, or the woman can be offered duloxetine (a type of antidepressant) if she does not want to consider it or is not suitable for surgery.

Conclusion

There we have it, from types of urinary incontinence to assessments and management to complications – everything you need to know to be OSCE prepared!

We want to thank Dr Patrice Baptiste for her time and excellent advice, and we look forward to bringing you many more articles that will support your learning experience.

For more revision resources, why not check out our Urinary Revision Guide

Related Products

View All