Written by: Zak Shah, 3rd Year Medical Student, UCL.

Effective Communication with Children in Hospital

Being a doctor means training for years, absorbing dozens of textbooks worth of knowledge, and learning drugs, interactions, and side effects. But when faced with little and cute patients, how do you communicate effectively?

The doctor’s office or the hospital can be scary and intimidating for young patients, with an unfamiliar environment and many noisy machines. There will probably be lots of different faces, from the receptionists and other patients to the nurses and the doctors. Knowing how to talk to children can be challenging, so we’ve put together some tips that may help with effective communication with children in the hospital.

Talk to the child

An easy mistake to make when having a consultation with a child is to talk to the parents or carers of the child instead while ignoring the child during the consultation. Depending on the age of the patient, of course, it can make all the difference if you involve the child in their own healthcare. For younger patients, you can start consultations by asking, “Do you know why daddy brought you here to the doctors today?” for example. You may be able to pick up new symptoms that the parents/carers have not caught themselves, but equally importantly, you establish trust between yourself and the little patient, making them feel relaxed and in control of the situation – to quell their panic. Crucially, this allows these patients to grow up confident in taking responsibility for their own health so that they have greater trust in the doctors when they are older.

For teenagers and older children, the majority of the consultation should be between you and them. Although parents may be keen to do the talking, give teenagers the opportunity to explain their symptoms. They may not have told their parents the whole set of symptoms, and their parents may not know the full story.

By talking to the child and including them in their consultations, you allow them to develop autonomy regarding their own care and help to establish trust.

It’s okay to play around!

The joy of working with children is that it’s totally okay to drop the uptight mannerisms of a finely educated academic and have some fun – without being judged by society. But play isn’t just for fun. In fact, particularly with younger children, play is such an important way to break ground. Take a minute out before you start your consultation to play a little game with your young patient or demonstrate a magic trick which can dissolve the scary image of a doctor that the child has in their mind. The children will be more relaxed and comfortable, and procedures such as taking blood will be much easier for you with less wriggling and running away. Playing also reduces feelings of anxiety children may have when coming to an unfamiliar and scary setting and makes the experience much more pleasant for the patient. Children have so much energy – for the first few moments of your consultation, you can relax a little and match their energy to let them know that they can trust you.

Let the children help you out

Whether you are carrying out a procedure like a blood test or conducting a paediatric examination, you can get the children to feel more at ease by asking them to help you do your job. For example, you can ask the children to hold the piece of cotton wool while you inject them and pass it to you afterwards so that you can cover the injection site. Asking children to ‘help you’ hear their heart sounds with your stethoscope can make them feel important and establishes them at the centre of their own healthcare, making the doctor-child relationship one that is trusting and respectful.

Free Download PDFs

View AllShow children a ‘visual board’ at the start of the consultation or procedure

The hospital can be a daunting place, with unfamiliar people and machines for adults, let alone children. Visual boards are ways of presenting information in simplified visual formats that can help worried patients understand their surroundings. You could have a visual board with various pictures that show the sequence of everything the child will see or experience in their examination, starting from the very beginning of entering the hospital. For example, the first picture could show a hospital receptionist with a number one next to it. Number two could be the doctor’s door, which the child would have just walked through. Picture three would be the doctor’s chair that the patient would sit on, and so on, with the final picture being a picture of a sticker that a child will receive after the examination is complete.

Displaying this visual board to the children at the start of the examination can remove the confusion surrounding the consultation and helps the child to easily know what to anticipate next in the examination so they are not worried. The fact that children can see on the visual board that they will get a sticker at the end of the consultation reassures them that there is something waiting for them for their good behaviour at the end and should help them stay calm throughout.

Talk at their level

While younger children may like to be spoken to in a more fun and playful tone of voice, patients who are developmentally at the age of teenagers may find this patronising and may feel disrespected. Older teenagers should be spoken to with the same respect that you would show as if you were speaking to an adult, although time should be taken to explain some concepts in more detail if they are likely to be unfamiliar with them.

Listen to parents

Although tip number one was to speak to the children themselves, children can be shy or may want to hide the extent of their symptoms to appear tougher or out of embarrassment. In the majority of cases, parents or carers know their child best and will be able to give an accurate history and describe symptoms. It is often said in paediatrics that when a mother of a child with complex health needs has a gut feeling that something is wrong, the mother is usually correct. Listening to parents will save you time in reaching a diagnosis and will often allow you to treat your patients based on more accurate symptoms.

Talk about things not related to the child’s condition

You can help distract the child from the scary environment of a healthcare setting by asking them about anything else that is not related to their health or illness. For example, you could ask them about their favourite superhero, how school is going, or what artwork they have done at home recently. This helps the child to be in a good frame of mind for the procedure or consultation and can help you to gain their trust as a clinician.

Our final tip for communicating and working with paediatric patients is to work for a child’s smile. Paediatrics is a demanding career but seeing a child smile and want to hug you makes the job all worth it! With our child simulator, you can practice examinations and procedures such as OP airway insertion on a realistic child mannequin.

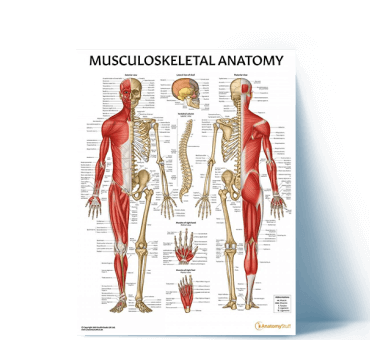

Feel free to print our many related PDFs and hand them out to the children for entertainment on their visit to the doctor!

Related Products

View All