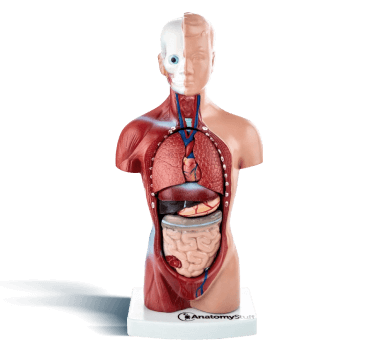

Introduction

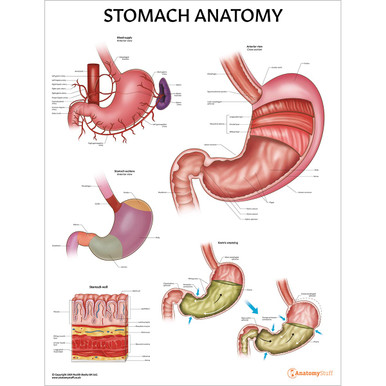

The stomach is a hollow muscular sac that is part of the digestive system. It is continuous with the oesophagus proximally and the duodenum distally. It performs many life-sustaining functions, such as the bulk storage of undigested food, the mechanical breakdown of food and the production of important acids, enzymes and hormones. Keep reading to learn more about the anatomy of the stomach, including its curvatures, sphincters, neovascular supply and much more.

Location

The stomach is located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, below the liver and next to the spleen. It lies between the oesophagus and the duodenum and is covered and connected to other organs by the peritoneum (a continuous membrane which lines the abdominal cavity).

Greater and lesser omentum

The omenta are large folds of the visceral peritoneum. There are two types; the lesser omentum, which connects the stomach to the liver and the greater omentum, which spans from the greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse colon.

The stomach also contains peritoneal ligaments, which are double layers of the peritoneum. They connect organs to other organs or organs to the abdominal wall.

Size

The size of the stomach varies depending on the body’s position, the respiration phase and whether it is full or empty. In general, its total volume is approximately 2L in adults.

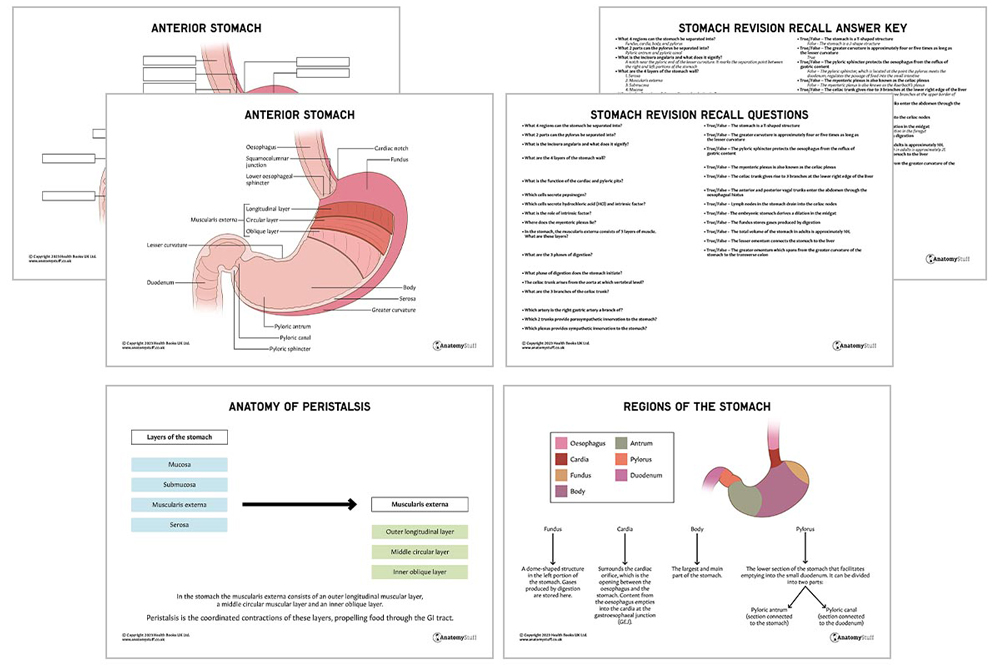

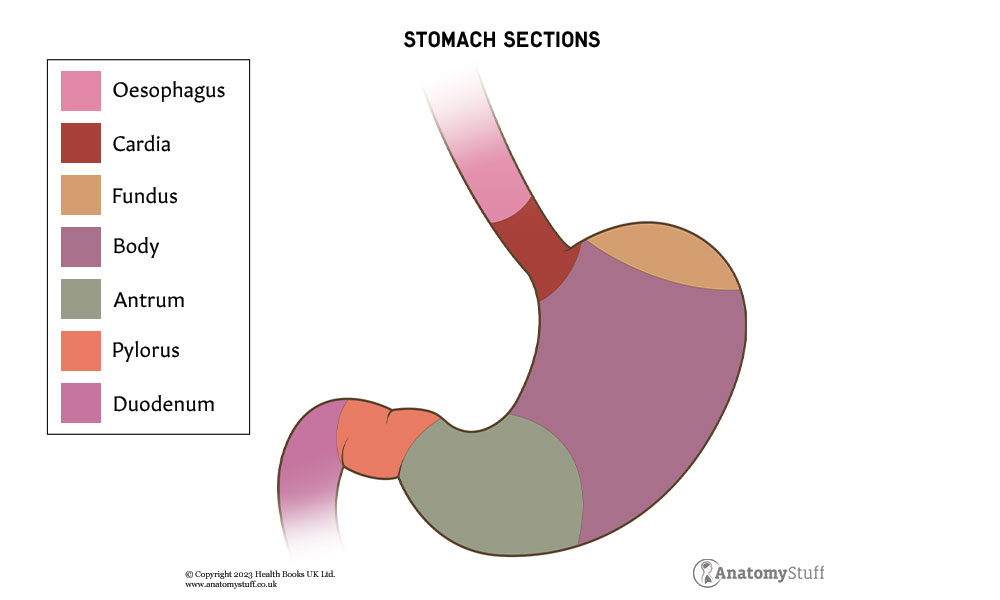

Regions

The stomach can be separated into four regions; fundus, cardia, body, and pylorus.

• Fundus: A dome-shaped structure in the left portion of the stomach. Gases produced by digestion are stored here.

• Cardia: Surrounds the cardiac orifice, which is the opening between the oesophagus and the stomach. Content from the oesophagus empties into the cardia at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

• Body (corpus): The largest and main part of the stomach.

• Pylorus: The lower section of the stomach that facilitates emptying into the small duodenum.

The pylorus can be divided into two parts – the pyloric antrum and the pyloric canal. The pyloric antrum is the section connected to the stomach, and the pyloric canal is the section connected to the duodenum.

Curvatures

The stomach is a J-shaped structure with two curved borders known as curvatures.

The greater curvature is the convex border located on the left side, and the lesser curvature is the shorter and concave border on the right side. There is a distinct notch near the pyloric end of the lesser curvature called the incisura angularis. It marks the separation point between the right and left portions of the stomach.

In general, the greater curvature is approximately four or five times as long as, the lesser curvature.

Surface

The stomach has an anterior and posterior surface which are both covered with peritoneum.

Sphincters

Sphincters are circular muscles that open and close passages within the body. The lower oesophageal sphincter is located at the top of the stomach, protecting the oesophagus from the reflux of gastric content.

The pyloric sphincter, which is located at the point the pylorus meets the duodenum, regulates the passage of food into the small intestine.

Refresher

Four smooth muscle sphincters are throughout the digestive tract: lower oesophageal sphincter, pyloric sphincter, ileocecal sphincter and internal anal sphincter.

Histology

The stomach wall consists of four layers of tissue. This arrangement is the same throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract; each layer helps the stomach perform its vital, life-sustaining functions. From superficial to deep, these layers are:

• Serosa

• Muscularis externa

• Submucosa

• Mucosa

The inner lining of the stomach, the gastric mucosa, is formed by a layer of simple columnar epithelium, an underlying lamina propria (connective tissue layer containing blood and lymphatic contents) and muscularis mucosae (a thin layer of smooth muscle).

The epithelium forms numerous tiny holes called gastric pits. These gastric pits are important as they are connected to the various glands of the stomach: cardiac, gastric and pyloric glands.

| Glands | Location | Role |

| Cardiac | Beginning of the stomach | Secrete mucus, which coats the stomach and protects it from self-digestion by helping to dilute acids and enzymes. |

| Gastric | Centre of the stomach | Produce most of the digestive substances secreted by the stomach. They are composed of 4 major cell types (see below). |

| Pyloric | Terminal portion of the stomach | Secrete mucous, which coats the stomach and protects it from self-digestion by helping dilute acids and enzymes (like the cardiac gland). |

Gastric glands are made up of different cell types:

| Cell type | Role |

| Neck mucous cells | Secrete mucus |

| Chief or zymogenic cells | Secrete pepsinogen (inactive form of pepsin), which is needed to digest proteins |

| Parietal or oxyntic cells | Produce hydrochloric acid (HCl), also called gastric acid, which is necessary to activate the other enzymes and a protein called intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the terminal ileum |

Gastric mobility

The muscularis externa is responsible for the contractions and peristaltic movements throughout the GI tract. The stomach consists of an outer longitudinal muscular layer, a middle circular muscular layer and an inner oblique layer.

Between the muscle layers lies the myenteric plexus, also known as the Auerbach’s plexus. This network of nerves contains the interstitial cells of Cajal, which control peristalsis, allowing food to travel through the GI tract.

Interesting fact

The muscularis externa usually contains two muscle layers only – the outer longitudinal and inner circular. The stomach contains an extra layer, the inner oblique layer, to help churn chyme (partly undigested food).

Phases of digestion

There are three phases of digestion; cephalic, gastric and intestinal. The stomach initiates the second phase.

Blood supply

The stomach has a rich arterial supply derived from the celiac trunk. This is the first major branch of the abdominal aorta at the vertebrae level of T12-L1.

Although the celiac trunk has several different branching variations, it commonly gives rise to three branches at the upper border of the pancreas: left gastric artery, splenic artery, and common hepatic artery. These arteries supply the foregut (upper duodenum, liver, gallbladder and biliary tree, spleen, pancreas, greater omentum and lesser omentum).

The gastric arteries, which arise from all three branches of the celiac trunk, specifically supply the stomach:

- The left gastric artery is one of the three direct branches

- The right gastric artery is the first branch of the common hepatic artery

- The left gastroepiploic artery originates from the splenic artery

- The right gastroepiploic artery arises at the bifurcation of the gastro-duodenal branch of the hepatic artery

The corresponding veins drain into the portal system.

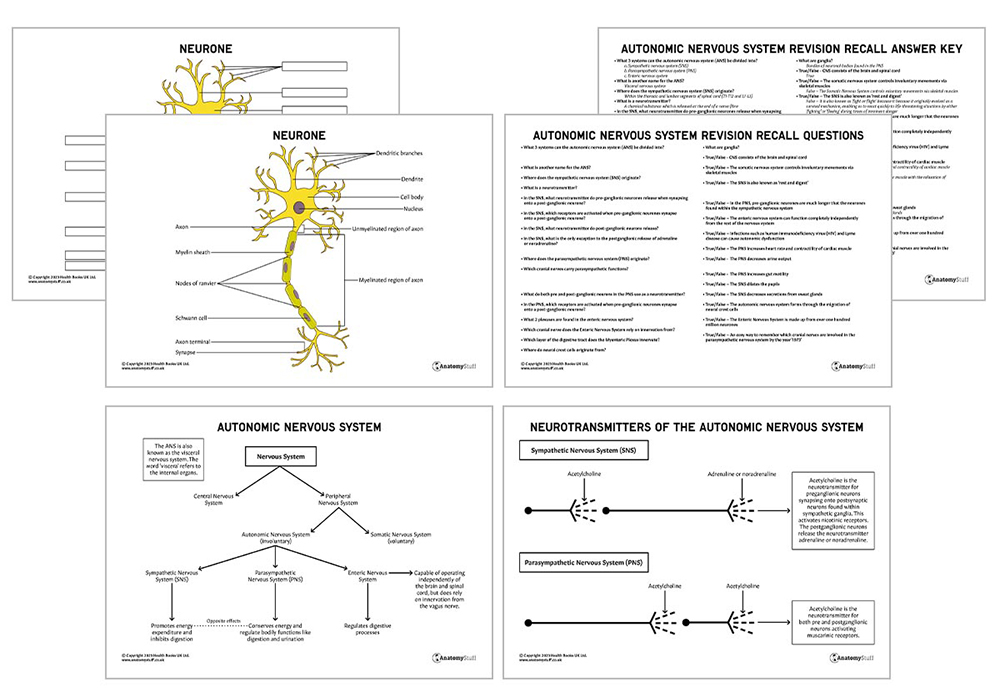

Innervation

The stomach receives innervation from both the parasympathetic and sympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system. Our autonomic nervous system. revision guide is packed with tips and hints to help you revise for those important exams!

Autonomic Nervous System Revision Guide Digital Download

Parasympathetic innervation to the stomach arises from the anterior and posterior vagal trunks, which enter the abdomen through the oesophageal hiatus. These are derived from the vagus nerve, the longest nerve cranial nerve in the body.

Sympathetic innervation to the stomach arises from a nerve network called the celiac plexus, the largest sympathetic plexus in the body, which surrounds the celiac trunk.

Lymphatic drainage

The stomach is drained by an extensive lymphatic network, including:

• Hepatic lymph nodes

• Left gastric lymph nodes

• Pancreaticosplenic lymph nodes

• Gastroepiploic lymph nodes

• Pyloric lymph nodes.

These groups of lymph nodes drain into the celiac nodes, which then open into the cisterna chyli (a lymphatic reservoir to the right of the aorta) before entering the thoracic duct.

Embryology

The embryonic stomach derives from a fusiform (spindle-like) dilation in the foregut endoderm during week 4 of gestation.

Refresher

The Primitive gut tube develops during weeks 3-4. The tube is divided into 3 distinct sections; foregut, midgut and hindgut, based on their arterial supply:

- Foregut derivatives in the abdomen are supplied by branches of the celiac artery

- Midgut derivatives are supplied by branches of the superior mesenteric artery

- Hindgut derivatives are supplied by branches of the inferior mesenteric artery

The foregut gives rise to the trachea, lungs, oesophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas and upper duodenum.

The midgut gives rise to the lower duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon and proximal 2/3 of the transverse colon.

The hindgut gives rise to the distal 1/3 of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum.

Related Products

View All